Creating journey maps to improve your content strategy

In a previous post, I wrote about how communication professionals can use design thinking to improve an organization’s strategies. Design thinking allows teams to broaden their perspective by learning about their users’ needs. Teams can then redefine problems from their users’ point of view, generate fresh ideas, and test prototypes with the people who will use the final product or service.

By creating solutions with rather than for your users, you increase the chances of creating something that’s valuable to them and valuable to you.

Unfortunately, design thinking makes many organizations uncomfortable. It asks them to acknowledge their blind spots, adopt a beginner’s mindset, and work across silos to create solutions that often challenge the status quo.

So how can we introduce design thinking in a nonthreatening way? One inexpensive but powerful method is journey mapping.

Journey mapping typically happens at the beginning of a design thinking process:

A design thinking model for business managers. The diagram is from Jeanne Liedtka and Tim Ogilvie’s Designing for Growth: A Design Thinking Tool Kit for Managers.

Creating a journey map gives teams a way to identify customers’ pain points within services, processes, and systems. In this blog post, I’ll describe how to create a journey map and how it can help improve your content strategy. But first, let’s take a moment to discuss what journey maps can do and how they’re different from other tools.

Journey maps vs. task analyses

Journey maps and task analyses are diagrams that describe the steps in a process. Both tools help teams understand users’ goals and how users succeed or fail at achieving those goals.

It’s helpful to map out these processes because most organizations create their products and services through team efforts. This allows employees to specialize, which creates business efficiencies. But it also creates blind spots, since no single person could possibly have a full understanding of every process.

Task analyses

Task analyses are great for exploring a single task from a single user’s perspective. The analysis shows exactly what hoops the organization is asking users to jump through.

If users are abandoning your online shopping cart, failing to complete online forms, or struggling to find information that you’ve tried to highlight, chances are good that a task analysis can help you determine what’s causing the problem and how to fix it.

A simple, hand-drawn task analysis from The User Experience Team of One: A Research and Design Survival Guide. Task analyses illustrate a single task from the perspective of a single user. CC by 2.0

Journey maps

Journey maps (also called process maps and service blueprints) help organizations describe the user experience, too, but on a far larger scale.

While a task analysis looks at an activity from the perspective of a single user, a journey map looks at a large-scale process, system, organization, or environment from the perspective of all participants.

In order to map each participant’s “journey” through a process, teams typically need to interview participants to learn about how they interact with the process. Journey maps build empathy by revealing the demands and expectations that customers, employees, and organizations bring to the process. Pain points are often the unintended and unacknowledged consequences of other business decisions. Mapping exercises can create opportunities to nudge organizations toward constructive self-reflection, and they serve as concrete reminders about problems that are otherwise “invisible.”

But perhaps the most important benefit is this: By showing how the parts of a system are connected, journey maps help organizations change the way they think about customers, employees, and third-party actors. A business process or service that creates a poor experience for employees often leads to a bad experience for customers. Everyone who interacts with the process is in a sense one of the “users.”

In other words, a company’s “front stage” and “backstage” must work in harmony to create positive experiences with their customers:

Customers interact with an organization’s “front stage,” which in turn relies on the organization’s “backstage.” From “Service Design: Internal Processes for Great Customer Experiences”

Everyone has a role to play, and everyone is connected. To keep the performance running smoothly, you have to understand what each actor needs, regardless of whether the actor is a prospective customer, a front-stage sales representative, or a backstage accountant.

How journey maps can help with content strategy

Journey mapping is important to content strategy because our content crosses so many boundaries. Few of us may have the opportunity to travel between an organization’s cubicles, workstations, warehouses, sales floors, and boardrooms every day, but our content goes everywhere—across offices, countries, and continents, through websites, intranets, mobile devices, e-mail, social media, webinars, advertisements, white papers, training materials. . . you name it.

Meanwhile, we create content at all levels of an organization, customers create “user-generated content,” and we borrow content (“curated content”) from other organizations.

Content is one of an organization’s most valuable assets, and yet it is often created haphazardly in silos, without much thought about how it should be created, who should be responsible for it, or what purposes it should serve. If you want your content to be useful and professional, you need to invest in it, just as you invest in other products and services.

In particular, content creation needs clear objectives that align with business goals and users’ needs, a logical and sustainable workflow, quality standards, and continual evaluation and improvement. This requires not only a staff of professional communicators but also at least one person in a leadership position who can analyze the content ecosystem and make systemic changes that better serve the organization and the users.

Journey maps provide a convenient way of documenting the users, actions, and communication channels in content ecosystems.

In this diagram, the steps in a process appear alongside their corresponding customer touchpoints (e.g., internet, telephone, mobile device) and backstage participants. From Service Design: From Insight to Implementation. CC by 2.0

After documenting the current state, you can then track each user’s journey through the process:

The arrow traces a user’s journey through the process. From Service Design. CC by 2.0

This allows you to not only identify communication gaps, redundancies, contradictions, and inefficiencies but also trace them back to the organization’s underlying systems, processes, capabilities, and assumptions.

Sometimes you can resolve problems through relatively straightforward changes—by tweaking the roles and objectives of your teams, for example, or by adding or removing communication channels. Other times, you may need to rethink the overall process or system in order to create a better experience for users. Either way, a journey map will help you to identify root causes of problems and realistic solutions to those problems.

Case in point: How we used journey mapping to improve content strategy at a global NGO

I work at an international relief and development agency that has embarked on an ambitious plan to transform how it monitors and evaluates its overseas programs. Our agency works in partnership with local organizations around the world to help communities recover from emergencies, earn more through agriculture, and access quality health care. Like most organizations that do this type of work, we receive funding from a variety of institutions, each of which has different requirements for project outcomes and reports.

These differing expectations often make sense on the ground: for any two countries, the economic, cultural, civic, religious, and political context may be dramatically different. However, because relief and development organizations typically collect a different set of data for each project in the field, it is difficult for the international community to make comparisons across projects, countries, and regions.

My organization wants to change this. We’ve developed a set of global standards that are transforming how we collect data, evaluate projects, and learn from our work on a global scale. These standards become even more powerful as we work with organizations across the globe to help them adopt the same system.

We knew that change at such a large scale would not be easy, so we started by documenting the current state.

First, we interviewed the teams that were driving the process within our organization. We collected information about the objectives, participants, workflows, reporting structures, and decision-making processes that governed our organization’s original approach to monitoring, evaluation, accountability, and learning.

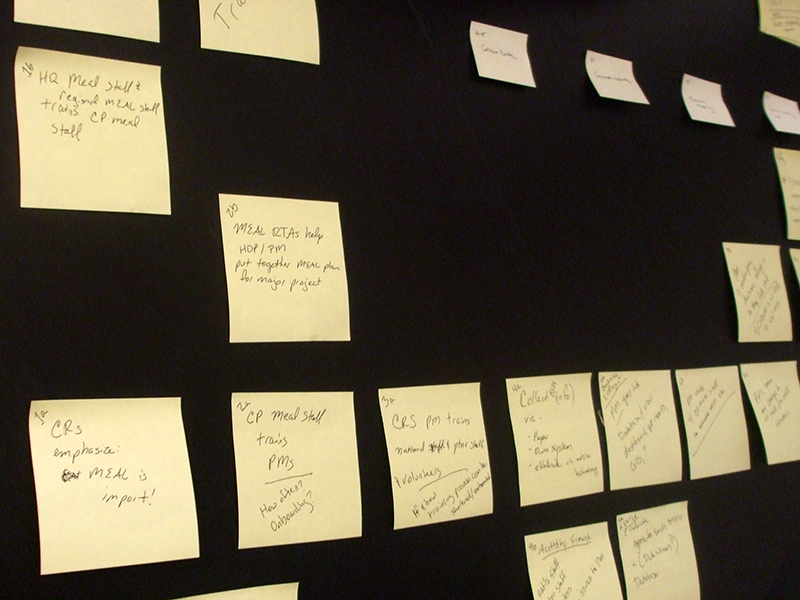

Each time we identified a new step in the process, we recorded it on a sticky note. Then we organized our notes in a formal journey map:

Our journey map. I’ve removed the content from the boxes because it’s currently considered internal information.

Each column represents a different phase in the process, and each phase includes multiple steps. The horizontal swimlanes group participants by role. The boxes and arrows describe who needs to do what in order to contribute to the process.

We took the journey map back to our groups of stakeholders and asked them to look for inaccuracies. Each team provided corrections about its part of the process. Even better, the teams began to ask questions about the parts of the process that were beyond their immediate control. By combining cross-divisional plans in a single document, the journey map revealed how teams could work together across silos to synthesize their individual plans—so the overall process would be more efficient for all participants.

As we identified participants and mapped the process, we also helped the teams develop a more unified content strategy and change management plan:

We proposed a revised rollout schedule and sequence of activities so the process would be more intuitive to all participants.

We identified the key executives, directors, and managers who would need to convey targeted messages at various stages of the process.

We selected online and offline communication channels to get the right information to the right people at the right time, without overcommunicating.

We found opportunities for cross-divisional coordination in order to consolidate training materials, avoid duplication, and streamline the training process.

We recommended that certain participants would prefer to use a simple spreadsheet tool rather than use a traditional publication in PDF form.

We recommended that a short list of key participants needed in-person training rather than publications for self-guided study.

We identified field-level employees who needed communication materials that they could use to train local partners.

We proposed how to establish a simple process for participants to submit questions and feedback.

The journey map made these conversations possible. It prompted teams to reconsider their approaches, and it revealed challenges and opportunities that needed cross-divisional planning and support. This created room to reevaluate what content needed to be created for which audiences and what purpose the content should serve. By finding ways to create a better experience for our stakeholders and users, we helped them set the organization on a path toward success.