Improving a digital ecosystem through content strategy

Remember when an organization’s digital presence was just its website?

Nowadays, even small organizations often manage a website, several social media accounts, an e-mail marketing platform, an e-commerce or fundraising platform, and a platform for managing relationships with customers or donors.

Bigger organizations commonly manage a slew of additional, overlapping, or even competing digital properties—separate websites (for various products, services, regions, or campaigns), mobile sites, microsites, apps, bots, digital asset management systems, and knowledge management platforms, to name a few.

As properties proliferate, they often get managed in silos, where they’re treated like tactical resources for individual business units. This typically creates disjointed and confusing experiences for users and employees. When users become frustrated, they seek alternatives, which ultimately hurts the entire organization.

Although organizations might prefer to manage properties in silos, each property actually needs to be designed and managed as a component within a digital ecosystem. A digital ecosystem includes not only an organization’s own digital properties but also properties that the organization doesn’t control. If your organization is narrowly focusing on creating and improving individual properties without thinking much about how they fit in the bigger picture, then it will be hard to thrive in increasingly crowded and complex digital ecosystems.

In this post, I’ll share how my team at IREX mapped our digital ecosystem, closed more than 65 digital properties, and aligned existing properties to better meet users’ needs.

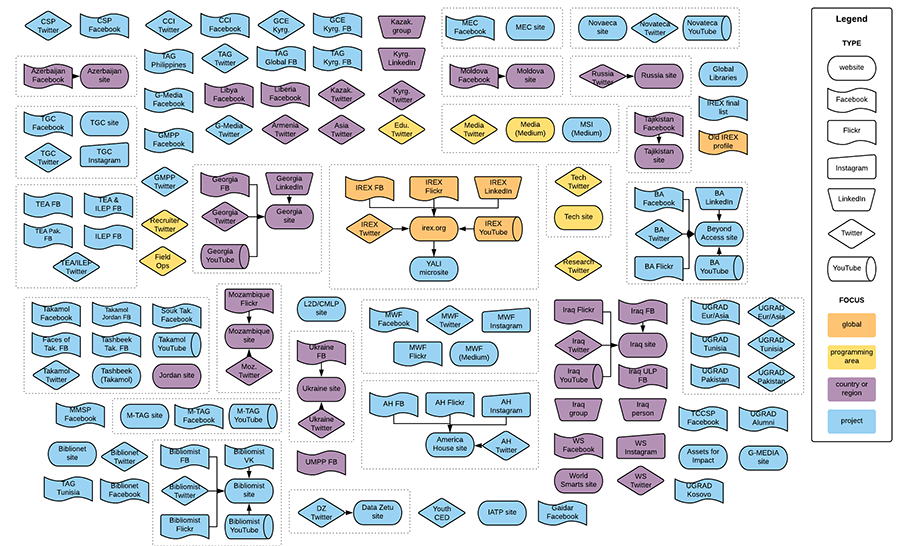

Creating a digital ecosystem map of our digital properties

When I joined IREX in 2015, we knew that teams within the organization had created a lot of digital properties over the years, but we weren’t sure how many properties existed. So we started by creating a master list of the websites, apps, social media accounts, and other external-facing digital properties that our organization owns. We created it in a Google spreadsheet so team members could compile the list together.

Then we visited each URL in the spreadsheet to look for links to other digital properties that weren’t on the list. For example, we often found links to social media accounts in websites’ utility navigation, footers, and “Contact Us” pages. We found links to websites in social media accounts’ bios and description pages. We also used the Content Analysis Tool to crawl large sites and find outbound links to other properties that we’d overlooked.

We ultimately identified more than 140 properties that the organization owned. During this early stage, we focused on identifying properties rather than on auditing them. But even so, a few things became apparent right away:

Some of the properties were quite active, but many of them were inactive.

The inactive and out-of-date properties were sometimes appearing ahead of the up-to-date properties in search results.

Among the active properties, there was a wide range of quality.

Each property generally focused on a narrow slice of IREX’s work—for example, by focusing on one region, one country, one issue area, or one project. (This can be problematic for a nonprofit like IREX that needs to demonstrate its impact to prospective donor organizations and partners.)

Many of the properties were primarily promoting content that the global-level properties and project-level properties had created.

It would be difficult for almost any organization of 400 employees to manage 140 digital properties. After all, that’s more than one property per four employees!

Since spreadsheets are not the most visually compelling of documents, we created a simple map of our digital properties:

This digital ecosystem map helped to make the problem more concrete when we met with teams to discuss the situation. If it was hard for internal teams to make sense of this digital ecosystem, then imagine how confusing it must be for external audiences who know much less about our organization.

Using the inventory and digital ecosystem map to inform our content strategy

Although the status quo was problematic, we knew that each property had been created for a reason. Often, employees had created properties in response to donor institutions’ requests and audiences’ perceived needs. In some cases, IREX was contractually obligated to set up particular websites and social media accounts.

However, when we observed that so many of the properties were either inactive or duplicative, we saw an opportunity to improve the experience for users while reducing costs, mitigating risks, and improving efficiency.

The inventory and map of digital properties directly informed our digital content strategy and roadmap. IREX’s strategic plan called for the organization to work across silos in order to improve effectiveness and build relationships with new donor organizations. The proliferation of properties had created significant technical debt, UX debt, and content debt that was holding the organization back and reinforcing old ways of working. So we made it a priority in our content strategy to consolidate our digital presence and align it to users’ needs.

We also recognized that the organization would need to agree to some digital guardrails in order to consolidate our digital presence, improve the remaining properties, and avoid sliding back into old habits. So our content strategy called for creating a digital governance framework and digital policies.

Our leadership team approved the digital content strategy and roadmap, and we began drafting a digital governance framework in collaboration with a cross-divisional working group.

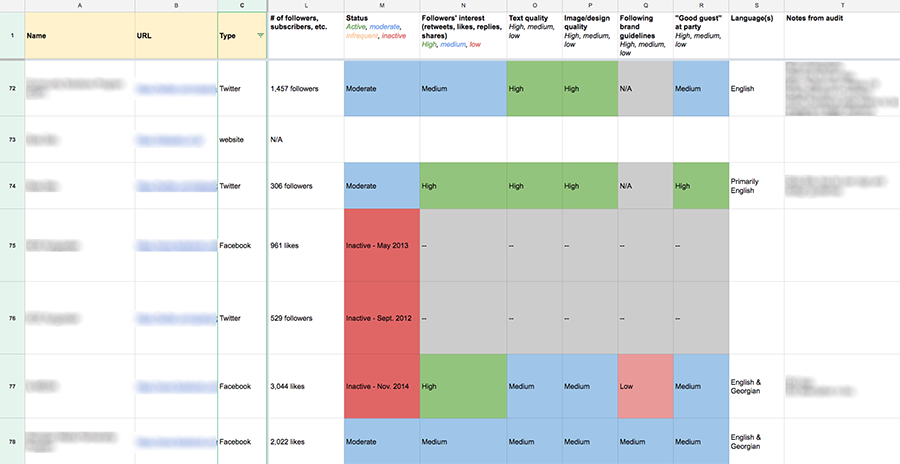

Auditing our digital properties and creating a plan

With work underway on the digital governance framework, we established a set of goals for our digital presence as a whole. We selected goals that aligned with our content strategy, which was itself the result of user research and stakeholder interviews.

For example, we knew that our digital presence would need to meet contractual obligations and help the organization implement certain projects. It also needed to align with IREX’s strategy while helping priority users complete their top tasks. Sometimes these goals seemed to pull in opposite directions. Therefore, we needed a solution that would balance these competing goals while improving the overall experience for users.

With our list of goals in hand, we took a closer look at each digital property in our inventory. We drafted a set of heuristics for an assessment.

For example, for each social media account, we documented the number of followers that it had, the amount of interest that the account seemed to be attracting from target audiences, how well the account was being managed (based on factors such as the frequency of the account’s posts, the quality of the text and images, the degree of alignment with our brand guidelines, and the quality of the account’s dialogue with audiences), the account’s primary languages, and related notes about contractual obligations and other considerations. We created a rubric for the qualitative components to promote consistency during the audit. (If you’re planning a similar audit, check out Abby Covert’s information architecture heuristics for a range of considerations.)

We reorganized our digital ecosystem map to group properties by focus. We ended up with four main groups: “global properties,” “issue properties,” “country or region properties,” and “project properties.” Although the situation was complex, these groups broadly reflected the intended purpose of the content in each group.

Then we used the audit to make tentative recommendations. We grayed out properties that we thought we should consider closing during phase 1 of the plan. Here are some of the reasons why we considered closing a property:

The property was inactive or abandoned.

The property received a low score during the heuristic evaluation.

Another property existed for a similar purpose.

The property conflicted with one or more of the goals for our digital presence.

The consolidated map that emerged wasn’t perfect, but it was a start. For example, we knew that some of the remaining “blue” and “purple” properties would reach the end of their lifecycle within about twelve to eighteen months as older projects wrapped up. In the meantime, as IREX bid on new opportunities, we worked with teams to incorporate a set of design principles into proposals so projects could plan digital properties in a more user-centered and sustainable way in the future.

One of the trickier questions was how to handle some of the larger social media accounts that had been created to serve the organization’s old strategy. Some of these accounts had a few thousand followers (a relatively large number for a typical account at our organization but a fraction of the following of our main accounts).

We wondered whether the accounts were reaching different audiences or whether they were essentially duplicating each other’s efforts (e.g., by showing the same content to the same users over and over again). To answer this question, we used ScoutZen to export a list of the followers’ handles. Then we compared the lists in Excel to identify duplicates. We found a much higher degree of duplication than we expected. For example, 71% of the people who followed one of the organization’s satellite Twitter accounts also followed IREX’s main Twitter account. When we considered this alongside the results of the assessment and our goals for our digital presence, we decided that it would be counterproductive to continue operating the satellite account.

Meeting with teams to discuss options

We used the analysis to start conversations with teams that managed digital properties. Some of the conversations were quick and easy. For example, few people thought it made sense to keep open inactive properties for projects that had ended years ago. A number of managers thanked us for helping the organization streamline its digital presence and reduce unnecessary work for staff.

When the conversations were more difficult, we tried to focus on learning more about teams’ objectives and constraints. Sometimes this new information changed our recommendations. At other times, the discussions helped us suggest different solutions to address underlying needs while bringing more order to our digital presence as a whole. For example, when we proposed closing an active property, we suggested ways for the team to reach its audience even more effectively through a more established channel.

By the time that we had these conversations, we also had a first set of digital policies in place, including a policy about retiring or improving underperforming properties. The policies provided institutional support to the initiative as a whole, while clarifying who was ultimately responsible for which types of decisions.

Creating an inventory of third-party properties

So far in this post, I’ve focused on how we created and implemented a plan for the digital properties that IREX owns. But what about all of the other properties on the internet that might be even more important to our target users? We wanted to make sure that we were meeting audiences where they were instead of narrowly focusing on just the properties that we could directly control.

Once again, it helped to make a map.

This map shows some of the main types of actors (in blue) and platforms and channels (in orange) in our industry. The platforms and channels are intermediaries between users and organizations: Users interact with certain platforms and channels to do their work. Organizations participate in these digital spaces in various ways—as authors, owners, moderators, or observers, for example.

In the above map, we could easily add dozens of names around the orange and blue lozenges, and we’d just be getting started. The map has been a reminder that IREX is just one organization in a complex industry. We are not the center of the universe for our target audiences, and our digital properties are not the center either.

Using the map as a reference point, we compiled a spreadsheet of major websites, discussion lists, newsletters, and other third-party properties that are influential in our industry. We also searched for third-party sites that mentioned IREX and added them to the spreadsheet as well.

This gave us a preliminary list of places where important conversations are happening about our industry or about IREX. It was a long list, so we selected a subset of high-priority properties for a first round of consideration. Then we created a brief plan for each property on the short list.

For example, there are a number of important directories where potential donors and partners learn about development organizations. IREX was missing from some of the directories, and our information was out of date in others. So we enlisted the help of our communications intern to contact the directories one by one and request changes. Within a few weeks, more than 85% of the directories that we contacted had updated their information about IREX.

There is much more to do, both for the properties that we own and for the third-party properties on our list. But by creating inventories and maps of our digital ecosystem, we’ve been able to identify problems and opportunities at the macro level and systematically work to improve the situation, in alignment with user research and the organization’s strategy.

More resources

If you’re interested in doing this type of work for your organization, I recommend Scott Kubie’s series on content ecosystem maps (“An Introduction to Content Ecosystem Maps,” “What to Include in a Content Ecosystem Map,” and “How to Use a Content Ecosystem Map”), along with Hilary Marsh’s “Developing Your Content Ecosystem” (both the article and slides).

If you’re building a system to reuse content at scale, see Mike Atherton and Carrie Hane’s Designing Connected Content and Ann Rockley’s Managing Enterprise Content.

The opinions expressed on this blog are my own and do not express the views or opinions of my employer.